Editor’s Note: FCO Member and Executive Director of The Conservation Angler, David Moskowitz, shares data and analysis of the 2023 Columbia River Steelhead run and has some solemn predictions for 2024. If you care about steelhead migrating up the mighty Columbia, these data are important to understand for your advocacy efforts. LKH

Looking Back, Looking Forward

As previously reported, the 2023 Columbia River Steelhead return was much better than the predicted forecast from fishery managers with an actual return of 33,600 wild steelhead past Bonneville – almost 13,000 more wild fish! If you are going to be wrong, it is good to be wrong in the right direction!

Nevertheless, the frequent forecast inaccuracy should set off some alarm bells for the fish agencies because these forecasts set the stage for commercial, tribal and sport fisheries – and sometimes these fisheries are opened before the agencies have any feedback on the actual returns.

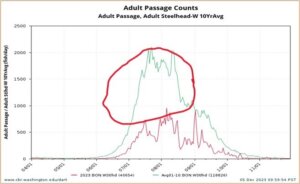

2023 Revised Summer Steelhead returning to the Columbia River above Bonneville Dam[1]

There have been some revisions in the counts from our December 2023 report. Fish Biologists revise the visual counts at the dams with actual determination whether an unclipped fish is wild or hatchery-origin.

Total Summer Steelhead Passage: April 1 thru November 30 – 2023

- 113,891 combined hatchery and wild steelhead (H + W) past Bonneville Dam

- 40,654 total unclipped steelhead passed Bonneville Dam [See Note]

- 33,600 total wild steelhead past Bonneville

Note: 17 percent of the unclipped steelhead passing Bonneville are unclipped hatchery-origin steelhead

- Current 10-year average steelhead passage (2013-2022) is 159,571 (total hatchery & wild steelhead).

- The current 10-year average for wild or unclipped steelhead passage is 58,162 summer steelhead.

Comparing passage with the Current Ten-year Average (CTYA) (2013-2022):

- The 2023 return of combined wild and hatchery steelhead is 71% of the CTYA.

- The 2023 return of wild summer steelhead is 58% of the CTYA.

- Hatchery steelhead outnumbered wild steelhead by some 43,247 fish.

To avoid the declining baseline syndrome, we must compare current run-size with a longer data period or with a more productive period to compare the overall loss of wild steelhead abundance:

The “best” decadal average return of total steelhead since 1984 occurred between 2001-2010 (410,370 steelhead (H+W). The BTYA for wild steelhead since 1984 also occurred from 2001-2010 (118,257 wild steelhead). Thus, the current 2023 return of total hatchery and wild steelhead is 39% of the BTYA. The current 2023 return of wild steelhead is 49% of the BTYA.

Comparing Columbia River 2023 Wild/Unclipped Steelhead returns with Best 10-year Average.

The circle is the “missing middle” representing the loss of Columbia wild steelhead since 2001-2010 (Editor’s Note: Apologize for the poor image reproduction, LKH)

Columbia Basin wild Steelhead face many challenges, but the current status of wild summer steelhead reflects an ongoing failure to set and meet spawning escapement criteria for Idaho, Oregon, and Washington wild steelhead rivers. Wild Steelhead diversity, spatial distribution, productivity, and abundance are affected by hatchery and harvest management in several ways.

Mainstem Fisheries:

Wild steelhead face non-tribal and Tribal commercial fisheries in the Columbia, sport fisheries in the Columbia and Snake Mainstem as well as Columbia and Snake tributaries where sport and tribal fishing is authorized.

- Even when limited, sport fisheries authorizing hatchery steelhead retention will also create lethal encounter impacts for wild steelhead that are not accurately observed or monitored.

- Tribal fisheries, by Treaty, may harvest, and by state action, sell wild steelhead caught in platform, set net and drift gill net fisheries throughout the Columbia and Snake and in tributaries.

- Monitoring and reporting are inadequate to accurately assess overall impact during authorized fisheries that enable managers to take precautionary in-season conservation action when steelhead runs are low.

- Summer Steelhead, particularly B-run steelhead, are harvested incidentally in non-tribal commercial fisheries and harvested directly in Tribal fisheries that are primarily aiming to catch summer and fall chinook and coho. Wild B-run steelhead are repeatedly caught and released in sport fisheries in the mainstem and in tributaries.

- Wild B-run steelhead migratory mortality is too high evidenced by calculating the loss of wild B-run steelhead between Bonneville and Lower Granite Dam due to harvest, fish passage mortality, predation, poaching and natural causes. In the last decade, the average percentage of wild B-run steelhead passing Bonneville but not reaching Idaho is 44.65%.

- Hatchery steelhead releases in tributaries throughout the three-state region compete with wild steelhead for rearing space and for forage. Mass hatchery releases also attract avian and fish predators throughout the migratory pathway and pose inordinate predation impacts for wild steelhead co-migrating with hatchery fish.

Sport Fishing Issues:

- Anglers may use bait, barbed hooks, and treble hooks when steelhead fishing in rivers where wild fish must be released. Catch and release mortality rates for bait are higher than for artificial lures and flies (This occurs in the John Day).

- Anglers fishing in boats may continue to fish even after reaching their limit, increasing the number of wild steelhead that face lethal and sub-lethal encounters and loss of energetics.

- Sport fishing for other fish species, even when closed for steelhead, can result in targeting steelhead.

- Wild steelhead are encountered more frequently in Columbia and Snake River tributary fisheries even though hatchery fish regularly outnumber wild fish by two or three to one (wild steelhead encounters frequently comprise half the reported angler encounters even though outnumbered by hatchery fish.

- Because most summer steelhead will not spawn until late winter through spring, their migratory behavior is less predictable and more likely to result in multiple angling encounters during their spawning migration.

- Fishing for steelhead is permitted in some rivers throughout wild steelhead staging and spawning activity from February to June.

Migratory Conditions:

- Steelhead rely on cold water refugia (CWR) during their migration. Once the water temperatures reach 68.5F, their residency and use of CWR increases from days and weeks to weeks and months.

- Wild steelhead relying on CWR are susceptible to angling pressures while they rest in the refugia – negating the conservation benefit of the CWR to migrating ESA-listed wild steelhead.

- Instream flows and augmentation flows are insufficient and are not prioritized to provide enough cool water when environmental conditions place migrating wild steelhead and salmon at elevated risk.

- Columbia River Thermal Angling Sanctuaries are essential conservation tools for wild steelhead.

And finally, the 2024 Forecasts – the early predictions are the highest since 2019.

To Bonneville, fishery agencies expect 126,200 combined hatchery and wild steelhead from April to Oct.

The Columbia River steelhead population is described as three components:

- Early summer steelhead = 4,000 combined H+W steelhead and 1,800 wild fish.

- A-run steelhead (fish under 78 cm) = 89,900 combined H+W steelhead with 32,400 wild fish.

- B-run steelhead (fish over 78 cm) = 32,200 combined H+W steelhead with 4,000 wild fish.

The total H+W return of 126,200 steelhead would be the 7th lowest return since 1984.

The forecasted return of 38,200 wild steelhead would be the 13th lowest return since 1984.

Even with the larger number, the 2024 forecast is the fourth lowest forecast since 1984.

David Moskowitz

[1] chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://wdfw.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2024-02/2024-spring-summer-forecasts-02142024.pdf