Editor’s Note: Guiding a child to develop a passion for fly fishing is a true joy. Watching the awe and excitement when my son enticed a huge Yellowstone trout on Slough Creek to a dry fly is a memory that I hold dear. Long-time FCO member, past President, and current Foundation Board member, Dr. Mark Metzdorff shares the beautiful and touching story of his son Alex’s growth as a steelhead angler. Thank you Mark for sharing such a touching and personal story. LKH

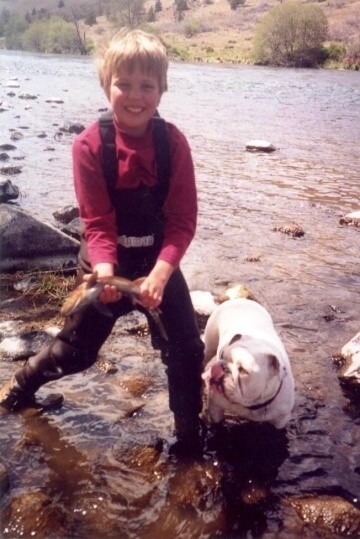

Alex Metzdorff, age 28 at this writing, has been an avid trout angler from his early youth. If the reader saves old, quality fly fishing magazines, check out Wild Steelhead and Atlantic Salmon ca. July 1998, in the “Reader’s Mailbox” section, for a description of his first Deschutes stonefly nymph-caught trout, and my rod-busting adventure trying to obtain a suitable photograph (Figure 1). Since then, his enthusiasm for trout angling has persisted in a manner very satisfying to a father equally fervent about the sport.

Figure 1. Young Alex Metsdorff with first trout.

For what are perhaps obvious reasons, his career as a steelhead fisherman began at a later age. The inherent difficulties in the pursuit, coupled with the infrequent reward of a connection with the quarry, led me to want to introduce this more challenging aspect of the angling spectrum in a gradual manner and at an older age. One doesn’t want to discourage a young angler, if at all possible.

An opportunity to imprint the thrill of a large fish on the end of one’s line arose as we fished the Deschutes in the fall near the Bachman/Dick Fitzpatrick homestead, Alex with a trout rod and I with my two-handed steelhead tool. Alex was about 12 years old. To my minor amazement, I hooked a steelhead in bright late afternoon sunshine, and after assuring that the fish was indeed well-hooked, I handed the long rod to Alex. He was thrilled and experienced the powerful thrumming head-shakes that the avid steelhead fisherman knows well. I instructed him to keep the rod tip up and toward the downstream bank, and to hold on while I ran to retrieve the camera.

When I returned just a few minutes later, I found out that I had neglected to tighten the drag, and as a result the fish had pulled out a good deal of line, presumably gradually, followed by what must have been a brief, brisk dash which resulted in a serious backlash deep in the running line. Surprisingly, the fish was still on. While Alex held the rod and tried to keep some tension on the fish, I worked the backlash out and got the fish back on the reel. From there, it was a matter of a few minutes for him to retrieve the fly line, as the fish was spent in the effort of fighting the enormous bow of line across the river. I tailed the fish, got a quick picture with Alex holding it, and we released her hopefully to fulfill her genetic destiny (Figure 2). At this point, I believe the steelhead hook was set in the lad as well.

Figure 2. Alex lands Deschutes Steelhead

It required some additional passage of time before the beginnings of teaching two-handed casting techniques; I suspect it was sometime in Alex’s early teens that this commenced, always on the Deschutes and in good, easily waded water. At some point during this era, I must have mentioned the oft-repeated conventional wisdoms that the steelhead was “the fish of a thousand casts,” and that “the average beginner can expect to spend 24 hours of casting time” before hooking their first steelhead. I know that this steelhead folklore made a big impression because, as our sessions on various parts of the Deschutes continued over several years, I realized that Alex was keeping track. “I’m up to 20 hours,” he said one time, anticipating only one or two more outings before finally hooking up. Unfortunately, it was about then that job considerations took our family to Denver, where never is seen an anadromous fish, although there are some avid steelheaders in that part of the west who travel great distances to feed their addiction (myself included, I soon realized). Although we visited our cabin in Camp Sherman one week each summer, there was not time nor inclination to spend a precious vacation day in the low-likelihood pursuit of a fish several hours away. The Deschutes would have to wait, and we had some great times on the Metolius, although at times those fish can be as rare as steelhead in the catching. Perhaps this too was a lesson in patience, well-suited to the developing steelhead angler.

As luck would have it, back in Denver an opportunity presented itself to continue Alex’s steelhead education, and in one of the most remote, spectacular and famous steelhead rivers: British Columbia’s Dean. I was able to arrange this because I had become friends with Jim Sirois, a wonderful, talented and complicated man who owned considerable property on the lower Dean, on part of which he had constructed a compound of log structures with his own hands, including a beautiful cabin. He spent roughly April through October there each year, and the rest of the year was based at his daughter’s house in Hillsboro, from which he pursued his passion of writing. Like most anglers who fished the lower Dean around the turn of this century, I had met Jim when he made the rounds of the campsites and lodges to chat up the occupants and peddle some of his books, all of which are quite good. In the course of our friendship I convinced him to speak to the FCO; in April 2006 he spoke on the subject of the bears of the Dean River, about which he was an expert. During one of our Oregon breakfast meetings around that time, he mentioned that I should bring the family for a visit to his cabin sometime. I never took advantage during our time in Portland, but in Denver I realized that this would be an opportunity not to miss; although strong and vital, Jim was in his early 80’s, and none of us knows what the future holds.

Figure 3. First steelhead on the Dean

The story of that trip could be another essay; but suffice it to say that it allowed me to further Alex’s experience with the two-handed rod and its target species. His casting improved markedly, and it was on the Dean in July 2011 that he landed his first ever steelhead at age 19 (Figure 3). By that time I think he had lost track of the hours spent fishing for steelhead, but I’d wager it wasn’t too much more than 24 hours total, so perhaps he confirmed the conventional wisdom. Besides a couple other steelhead that week, he caught a large and enthusiastic chum salmon that had, in addition to Alex’s cone-head Intruder, two other steelhead flies in its jaw. Another lesson: angling always surprises, every day is different.

Alex remained in Denver after college graduation, and we eventually returned to Oregon where I enthusiastically resumed regular steelhead trips to the Deschutes. For Alex, the minimal vacation granted to one low on the corporate totem pole precluded any joint steelheading trips; until, lo and behold, an unexpected benefit of the current epidemic was manifest. Because of Covid-19, Alex’s job required his working from home; and later he was permitted even to work from our home, which he began in May of this year. Among many other benefits, this allowed us to plan another long-hoped for father-son multiday steelhead trip. Prior to Covid-19, it was to have been a week in Skeena country, but that was out. Second choice, and a chance to break Alex’s Deschutes skunk, was a jet boat trip on the lower river for four nights out of a campsite below Mack’s Canyon. This outing turned out to be planned for the week where wildfire smoke inundated much of central and western Oregon. We went to the put-in ready to go, but the air was unbreathable for more than thirty minutes, and no clearing was in the forecast, nor did any occur for more than a week. Back to home, back to work.

About ten days later the air had cleared and we decided to do a day float between Beavertail and Mack’s campgrounds on the Deschutes. We stayed at the Imperial River Company in Maupin the night before so that we could get an early start and have some shaded water to fish for a few hours on what was to be a warm, sunny day. Although we did get our early start, it turned out that, on this Sunday after nearly two weeks of pent-up desires, many other steelhead anglers, guided and unguided, had the same idea; so we had only two runs to fish with a dry line in shade in the morning. No plucks, no tugs, no grabs, nothing.

Figure 4. Finally, a Deschutes steelhead!

Once again trusting the conventional wisdom, I changed our lines to medium sink tips with larger flies to fish in the bright sun. I chose a good-looking if difficult-to-wade run on river left that I figured not many typical anglers would fish and anchored the boat. We walked about fifty yards downstream, and I had Alex start casting above some obvious subsurface boulders in moderately deep water that to me smelled like steelhead. Sure enough, within about ten casts a fish was hooked. As usual, the first determination was, trout or steelhead? A brief roll of the fish didn’t show much but clearly this was a steelhead. After a brief, slow run by the fish put an impressive bow in Alex’s fourteen foot Burkheimer, another roll at the end of this spurt showed this to be a large fish, not a typical 4-6 pound Deschutes specimen. I thought it might be a fall Chinook and ran back to the boat to get the net. When I returned the fish was close enough to identify as a steelhead, and soon it was in the net (Figure 4). Although we didn’t put a tape on it, it was clearly north of thirty inches, and quite girthy; I estimate it was at least twelve pounds; and as a hatchery fish, it was either a second-spawn Deschutes plant or a B-run stray from Idaho. In either case, for its size, spunk, and significance, (and as it was early in the day and we had no ice) we decided to release Alex’s first Deschutes steelhead hooked and landed by himself.

Our elation and return to fishing in earnest soon gave way to dumbfoundment and dismay, as within the hour the river went out, completely opaque, presumably due to a White River event of unclear etiology, since it had been cool and without rain that I knew of within recent days. I can only chalk it up to “2020.” We fished hard with the biggest flies in my box until dusk without action, and by then had the river to ourselves as the wiser anglers had long since moved on. I count this as probably my luckiest day ever in steelheading

But that is not the end of the story. Two weeks later, and with great enthusiasm and anticipation on the part of some, we embarked on a hastily planned four-night float from Mack’s to Heritage Landing on the Columbia. Besides Alex and me, the party of two boats included my particular friend, former FCO President and lower river expert Dr Robert Sheley; and one of the best steelhead anglers I know, Stacy Barto, a former Babine River guide from back in the 1970s and 13-year camp companion from my annual week on the Babine River in BC. Stacy had never fished the Deschutes and was completely, as the kids say, “stoked.”

But as seems frequent if not inevitable in this plague year, fate once again had other plans. A river which had a nice color and 4-6 feet of visibility as we launched, within six hours had once again become the color and clarity of a cold cappuccino. At least this time we knew that the cause was a rain event on the White Glacier on Mt. Hood; hence we held out hope for some improvement over a four night trip, but it was not to be. The river seemed to get worse, not better, each day. Other than one fish hooked and lost on the first night as the river blew, no other piscine contacts ensued.

On the other hand, we had occupied two of the best campsites on the lower river; we ate and drank spectacularly; and had tolerably good weather with sleeping under the stars most nights. The fellowship was sublime, accompanied by an appropriate soundtrack. We were undoubtedly the first anglers in history to “glo-ball” the Deschutes for two evenings, albeit with similar success as our daytime fishing produced (ask me nicely with an offering of single malt, and I may elaborate). It was a good and appropriate introduction to the mysteries of the steelhead camp for a relative novice, and for that I’ll always be grateful. Or, as A. K. Best once wrote: “It was a complete success. We said we were going fishing, and we did.”

Dr. Mark Metzdorff